THE BIANWEN BOOK I-A GENEALOGY OF MY CULTURAL REFERENCES

The Bianwen Book I-A Genealogy of My Cultural References

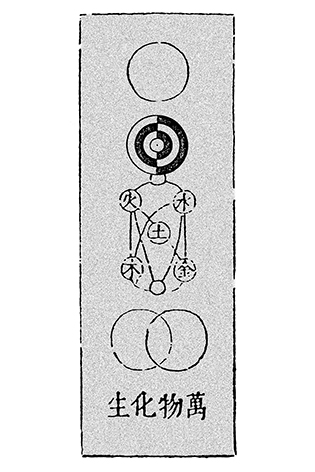

Bianwen and Sujiang Monks (Interpreting Sutras, Translation, Rewriting, and the Evolution of an Art Form)

Historical Background

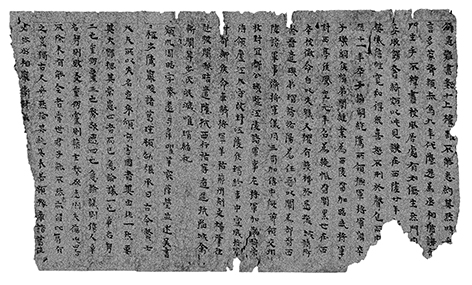

Bianwen is a Tang Dynasty (618—907) literary form that evolved along with the spread of Buddhism into China from India. To facilitate understanding among the common people, esoteric scripture was translated into the vernacular and then performed by Sujiang Monks. In their written form, these vernacular Sutras are called bianwen. Their popularity has resulted in their assimilation, transformation and development by folk artists since the Tang period, and therefore bianwen has inspired many operas, stories and novellas.

Contemporary Interpretation

These monks who interpreted, translated and rewrote Sutras were performance artists constructing a discursive field. But placing them in contemporary society would be to re-imagine or redefine their significance. They would no longer be interpreters, translators and re-writers, but crusaders for canonical theory, transformers of today’s complex political forms via demystification, or promoters of open ended stories and indefinite narrative forms.

A Smiling Anonymous Victim of Lingchi (Creating Confusion under Impossible Conditions)

Historical Background

The origins and meaning of the Chinese term lingchi (凌遲), which also refers to execution by slow dismemberment, has yet to be thoroughly studied. Textual research can verify, however, that the term has been used for both the demolition of tombs and erosion of hills[1]. On April 24, 1905, China officially abolished the use of lingchi torture. In his 1962 book Les Larmes d’Eros, French theorist George Bataille applied a philosophical treatment to a photograph of lingchi. Showing the victim looking skyward with a faint smile, the photograph is widely known among western intellectuals due to Bataille’s attribution of limit experience and erotic ecstasy to its subject. Furthermore, these concepts are most often cited by westerners when discussing lingchi. More recently, French sinologist Jérôme Bourgon, after careful study of historical photographs and other related materials, has cast serious doubt on Bataille’s claims.

[1] Brook, Timothy and Bourgon, Jérôme; Blue, Gregory. Death by a Thousand Cuts, Beijing: Commercial Press, pp.223-243.

Contemporary Interpretation

I believe this nameless victim’s smile signifies much more. He is bound and has no way to escape, then force fed opium until semiconscious, and photographed while his limbs are severed from his body. In this immobilized state, he uses just a smile and a camera held by a colonial soldier to create enormous confusion. The confusion then sets off discourse that continues to circulate around the image for years after he was executed. In this impossible situation, he managed to act, and his small gesture of a smile would never be erased by his death or by passing time.

Lo-deh Sao (Multiple Identities and Multiple Sites)

Lo-deh Sao (Multiple Identities and Multiple Sites)

Historical Background

In pre-industrial times, Min-nan farmers living in the Taiwan – Fujian region would sweep clean a spot in the village, perhaps under a tree, and perform simple operas during the non-growing season. This form of cultural production organized for villagers’ amusement was called lo-deh sao, meaning “to sweep the ground.” Along with the development of temple festivals, where statues and life-sized puppets of deities were paraded through villages, lo-deh sao became traveling performances featuring walking, performing and singing. Villagers often joined these traveling performances.

Contemporary Interpretation

In our increasingly atomised and alienated capitalist society, I believe lo-deh sao still has the power to inspire. In addition to being farmers, those performers took on the different identities of mythical figures or other characters they portrayed. Not only were farmers creating art during these performances, but more importantly, they were afforded an opportunity to transcend their identities; or it could be said that the multiple identities of farmer, performer (artist) and mythical figure converged in one individual. Furthermore, the performance spot became a mobile site of intersecting times and places. In China’s history of peasant uprisings, these performances were often used to rally the masses for revolution.

Bitai Thoan (Yaoyan Films and Strategies for Anti-Imperialist and Anti-Colonial Cultural Activism)

Bitai Thoan (Yaoyan Films and Strategies for Anti-Imperialist and Anti-Colonial Cultural Activism)

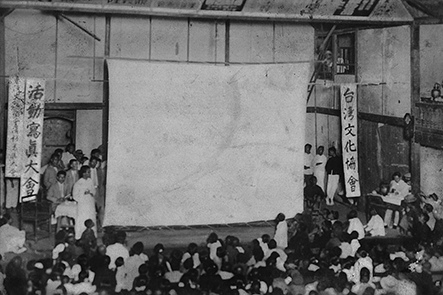

Historical Background

During Taiwan’s Japanese colonial period (1895—1945), Chiang Wei-shui established the Taiwanese Cultural Association, which operated from 1921 to 1927. The association formed a traveling team of projectionists and silent film narrators known as Bitai Thoan in 1926. At the time it was common for Japanese police officers or firefighters to be seated in the last row of theaters run by local Taiwanese. Their purpose was to monitor film narrators and prevent them from advancing anti-colonial sentiment. These same narrators, however, would use Taiwanese dialect, slang or sayings that only the local audience understood to deliberately create anti-colonial meaning in films where it never existed before. The audience would laugh, applaud, cheer and gesture when they heard these deliberately twisted interpretations. Even though Bitai Thoan only existed for two years, they were able to develop an effective, art-based protest strategy as early as 1926.

Contemporary Interpretation

The interaction between Bitai Thoan silent film narrators and their audience was a dialogic performance that both relied on images and went beyond images. This was especially so when the Japanese monitors left their high perch at the rear of the theater and stepped between the narrators and the audience to halt the interaction. At that point, the colonizers not only became visible to, and were encircled by, the audience, but also suddenly became the monitored under the gaze of the local people. Whether the Japanese police and firefighters successfully thwarted interaction is less important than the fact that each was forced into a dual role of colonial oppressor and the subject of scrutiny. The theater space intended for presenting films became the site of a role exchange between the monitor and the monitored, as well as a site where sound, image, dialog, theater and cultural action came together to create a complex dialogical art context.

Following these connections, we might imagine that those audience members charged with subjective agency would re-translate, re-imagine and re-narrate based on their own interpretations of a film originally intended as colonial propaganda. Through this process of continuous retelling, it would be possible to produce countless anti-colonial, yaoyan[1] films.

[1] The Chinese term yaoyan (謠言) originally referred to sayings or rhymes circulating in society that were critical of the government. Yaoyan was a strategy relying on poetic language, songs and fabricated narratives to disrupt authorial mechanisms and comment on social issues. As a result, it produced historical points of view and social imaginaries that deviated from official narratives.

Li Shih-ke (The Deprived Who Author Their Own Fate)

Li Shih-ke (The Deprived Who Author Their Own Fate)

Introduction

Li Shih-ke was born in 1927 in Changle County, Shandong Province, where he attained an elementary school education. During the Sino-Japanese War, Li participated in guerrilla warfare to resist Japanese fascism. After the end of the Chinese Civil War, Li retreated with Kuomintang forces to Taiwan in 1949. He retired from the Kuomintang army in 1959 due to illness. Alone and encountering many difficulties, Li did not manage to find a viable job until 1968 when he became a taxi driver. By 1982, Li felt that Taiwan’s distribution of wealth had become too unbalanced due to collusion between big business and government. His anger compelled him to rob Taipei’s Land Bank on April 14, 1982, which he did wearing a wig, hat, and surgical mask, and carrying a revolver he took from a police officer that he had killed in 1980. He fled with more than NTD 5 million in Taiwan’s first ever armed bank robbery. Li gave NTD 4 million to the parents of a neighborhood girl for her education and was apprehended when the parents reported the money to the police. Li was executed by firing squad on May 27, 1982. The details of his death aroused an inward sympathy for the man during the martial law period; a time when there was no free speech in Taiwan. In his 1982 article Wei Laobing Li Shike Hanhua (speaking out for veteran Li Shih-ke), the well known martial law period dissident Li Ao wrote about Taiwan’s countless veterans like Li who were forced by the Kuomintang to abandon their homes in China and serve in the army until they grew old or sick, and then left unattended at the bottom of society. For Li Shih-ke, robbing a bank was the only form of protest available against national mechanisms that stripped him of his life.

Premise

After the robbery in 1982, Taiwan’s three state supervised television stations repeatedly broadcast the incident as recorded by bank security cameras. These unclear images show Li Shih-ke wearing a wig, hat and surgical mask climbing over a teller station. Most media outlets at the time surmised that the robber was about 30 years old, and they only learned of his true identity, a 55 year old veteran, after the arrest. I remember watching the television news reports of Li’s arrest, including one where a television reporter carrying a microphone cornered Li and asked him why he robbed the bank. Li was only able to get out, “I have something I want to say…” before a policeman quickly covered Li’s mouth with his hand. Many years later, several television stations revisited Li’s case, but this scene of the police officer preventing Li from speaking never appeared, making me wonder if I imagined it. Perhaps those images of Li at the time of his arrest, with his calm demeanor and the traces of hardship on his face, sparked my imagination after they were projected into my mind.

To me that repeatedly aired footage of Li climbing over the bank counter represents a person who had been deprived of his life crossing an uncrossable boundary in order to get it back. And his disguise represents revealing what is behind the disguise, and forcing Taiwanese society to re-recognize the faces and fates of those countless people who were deprived of a life. Li chose not to silently endure an abject existence and die in martial law Taiwan, but instead chose to transgress by robbing a bank and take back his right—and the rights of other nameless veterans—to author one’s own fate.

If we separate ourselves from the view of identity imposed by colonial modernity and re-investigate the history of cultural production in Taiwan, then Li Shih-ke is a martial law successor to the Taiwanese Cultural Association of the Japanese colonial period, and a pioneering video artist and practitioner of relevant cultural activism. Despite his struggle in the lowest rung of society, which is devoid of the luxury and leisure to imagine whether his actions will one day be recognized as a form of cultural production, Li spoke out for a generation of people who had been deprived of their destiny, and had their individual sensibility repressed for so long, and did so during martial law when most intellectuals remained silent.

Cheng Bao-yu (A Context Constructed by Illiteracy)

Cheng Bao-yu (A Context Constructed by Illiteracy)

Introduction

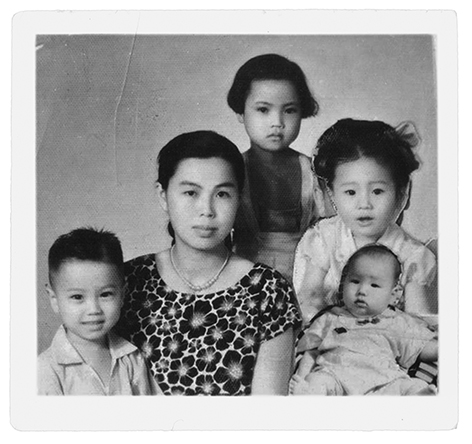

My mother Cheng Bao-yu was born in 1931 in Klang City, Malaysia. When she was 5, she was sent to a family in Kinmen as part of an arranged marriage. At the age of 7, she was left in the care of a widowed grandmother in Kinmen when the family emigrated to Indonesia. When she was 10, she picked seaweed and sold it to Kinmen’s Japanese occupiers to support herself and the grandmother. When 14, she made a living by gathering firewood and selling it to wealthy families for cooking. When 17, she set up a fruit and vegetable stall next to a well at Kinmen’s Dongmen Market. At 20, she started living independently. At 23, she married my father, who was a soldier at the time. After the 823 Artillery Bombardment[1] erupted in 1958, my mother left Kinmen with my older siblings and relocated to Neili, Taoyuan County, Taiwan. I was born in 1960 in Neili, and in 1962, she took us to live in Zhongxiao New Village in Shuiwei, Xindian City, Taipei County.

[1] The 823 Artillery Bombardment occurred between August 23 to October 5, 1958, between People’s Liberation Army and Republic of China troops located in Mainland China and Kinmen along with surrounding islands, respectively. Historians consider this to be part of the second Chinese Civil War.

Premise

When I was a child, whenever my mother talked about anything, she always started from when she was 5 years old. After talking for 2 to 3 hours, she would get to what she really wanted to talk about. I had no patience for my mother’s tedious way of talking about things when I was a child, but realized later that since my father worked away from home for much of the time, she had no one to talk to but us. She was illiterate and raising children alone and could only repeat her life story about not having a family and having to support herself since she was a child so that her children would never forget. I also didn’t realize until later why my mother, who had no social connections, planned for the future and finished things over 5 or 10 year periods.My mother was much like the many other women of the time who had no education. Whenever she encountered a difficult to solve problem, she looked toward the people, events or scenes that appeared in her dreams for answers. Before, I just thought this was her own way of justifying her decisions, but now understand that fantastic dreams, no matter how fantastic, are just another way of thinking about problems.Over the last several decades, my mother’s life story and her endlessly expanding dreams have found their way into my own consciousness. Or maybe my mother’s humble way of speaking and doing things has taught me something. She has taught me why the situation surrounding anything is important, and how to overcome the limitations of reality by continuously conversing with fabrications. She also taught me that when doing anything, you have to think about what its implications might be 10 years hence.I didn’t get married until I was 48 years old. After my son was born, my mother followed local customs and dressed him cotton gauze baby clothes. She said she had saved the clothes since I was born, and had been looking forward to using them again for 48 years.

Taking Control of a Factory—Hsinchu Glass Factory Worker (Autonomous Participation in Economic Democracy)

Taking Control of a Factory—Hsinchu Glass Factory Worker (Autonomous Participation in Economic Democracy)

Historical Background

Global neoliberalism increases income disparity daily in every place on earth. The idea of economic democracy has been raised once again. In 1986 when Taiwan was still under martial law, a series of managing investors of Hsinchu Glass Factory (52% of which was owned by the state) tried repeatedly to transfer assets out of the firm for their own benefit and seize control of the worker’s pensions and benefits. Their actions pushed the factory into serious financial difficulties, including debt to workers in the form of back wages. Ultimately, over 700 employees went to the government to see if it was possible to use an unregulated neighborhood credit club to raise funds and establish a temporary, employee-run regulatory board for the factory. After complex negotiations between managing investors and the government, the workers successfully took control. After 10 months, the factory generated enough income to pay all back wages, and even raised salaries. Due to the nature of the times, the temporary board had to return control to the managing investors after the factory got back on track, thus ending this period of economic democracy. Since these investors had no intention of running the factory, it closed soon after the handover in 1989. [1]

[1] For more information, see interviews and research conducted by Peng Kui-chih and others. This introduction was used with the permission of Peng Kui-chih.

Contemporary Interpretation

The take over of the Hsinchu Glass Factory during martial law by workers who had no training in leftist economic theories, made me realize that autonomous economic democracy can be successfully developed based solely on practical life experience and struggle. Their story started me thinking about possibilities for practical contemporary participatory democracy and economics. Due to global neoliberalism, any micro practice of economic democracy will encounter economic pressure from the region or country in which it takes places, as well as from the global flow of capital across national borders. Therefore, in any practice of economic democracy, one must consider types of products and production methods that will not be absorbed or canceled by transnational capital, as well as how to transform human desire constructs and lifestyle values. In other words, I learned the importance of self education from the autonomous development of economic democracy at the Hsinchu Glass Factory. Therefore, the practice of economic democracy at any site requires self education that transforms the existing consensus and desire construct.

Lien Fu Employees Self-help Group (Disabling the System with Its Own Rules)

Lien Fu Employees Self-help Group (Disabling the System with Its Own Rules)

Historical Background

Under pressure from the U.S. plan to end financial aid to the Republic of China in 1965, Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs promulgated its Statute for the Establishment and Administration of Export Processing Zone. Following the establishment of the Kaohsiung City Nanzih Export Processing Zone one year later, the island of Taiwan gradually became a global manufacturing hub. In 1987 when the order was given to end martial law, industries started moving abroad in search of cheaper labor, thus generating a series of bankruptcies to protect investors but rarely workers. These malicious factory closings reached their peak in 1996.

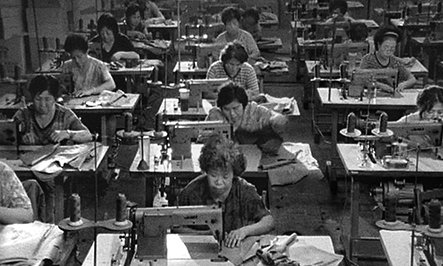

On August 16, 1996, The Lien Fu Garment Factory suddenly posted a sign on the door announcing its immediate closing. They hadn’t informed workers, and never disbursed worker pensions, severance pay or salaries. The factory owner made use of his dual citizenship to leave Taiwan and has refused to return. He still has yet to fulfill his obligation regarding worker rights and interests. Over 300 women workers who had worked in the factory from 20 to 30 years sewing clothing appealed to the Ministry of Labor and struggled for 12 years with assistance from the National Federation of Independent Trade Unions. They employed protest tactics such as shutting down the railroad by lying on tracks just to get the government and society to take their pleas seriously.

In 2008 the factory was auctioned off by the court. On November 11 of the same year, the new owners demolished the factory after the police had to forcibly remove women workers who were protesting at the site. These unemployed women lack the basic legal protection of the Taiwanese government, as a result, they still have not received the pensions, severance pay and salaries owed to them.

Contemporary Interpretation

Although these women protested for many years and never received justice, when they worked with me on my video Factory, I heard many stories revealing the profound folk wisdom they developed regarding protest strategies through this experience. From these workers I realized there is no such thing as an impenetrable system.

Following their continual and vehement protests, the Taiwanese government had no choice but to pursue subrogation, which requires the state owned bank to pay the women on behalf of the negligent factory owners. But several years later the state bank could not recoup the funds from the negligent factory owners and required the workers to return the money.

Facing great difficulty, the women forced the state bank to give up this preposterous requirement using a simple and legal strategy. These more than 300 workers assembled at the state bank and lined up at a single teller window. They each opened an account with NTD 100 and then returned to the end of the line so they could withdraw NTD 10. Each of these 300 workers went to the bank every day and repeatedly deposited and withdrew a small sum of cash, which wreaked chaos upon the bank’s system. In the end, this strategy forced the bank to give up on its dunning practices.

The women used what I believe is a legal mechanism: repetition that overloaded the system’s capacity and made it cease functioning. From a certain perspective, taking mechanization and repetition to their limits is a way to open a gap in the law.

Chen Chieh-yi (Self Reliance of the Poor)

Chen Chieh-yi (Self Reliance of the Poor)

Introduction

My brother Chen Chieh-yi was born in 1965. In high school he violated various ridiculous rules and was repeatedly expelled. He ended up attending three different high schools, and didn’t leave post-secondary school until 1992. He studied apparel and later worked at a clothing company, where he turned the failing business around in one year. The company wasn’t willing to give staff a raise, so he left the job. In 1994, without any savings, he found some fabric that was discarded by factory, hand made a few backpacks and started selling them on the streets of Taipei.

In 2002 I was fortunate to receive some financial support to make my videos. My brother and I decided if we could continue to make films, we should make films that would be regarded as actions by using local people, unemployed factory workers, temporary workers, migrant workers, foreign spouses, unemployed youth, social activists and different kinds of people employed in the film industry. Our goal was to break through divisions between amateurs and professionals and to create temporary, mobile and heterogeneous communities where participants could learn from one another. Since 2002, we have been producing film as action using this method, and have continually refined our organization methods.

Premise

My brother’s resourcefulness in starting a business with no money inspired my working method when I returned to making art. I think he not only knew how to use leftover or discarded things, but also how to create possibility from the impossible under limitations. His business experience inspired us to redistribute resources after they became available, which allowed those who were frustrated, discarded and oppressed by neoliberalism to regain their agency. And from these people who participated in my projects, we learned much folk wisdom and many ways of working with others.

I remember my father once gave my brother NTD 10 when he was in 5th grade. He didn’t use this pocket change to buy a toy, snacks or even save it. Instead he went to an old craftsman and bought a small bamboo flute. I asked why he bought a flute, since he didn’t know how to play one. He answered that he had been watching that old man for a long time, and no one ever bought anything from him. He thought the man needed the money more than he did. This was my first lesson about sharing and redistribution.

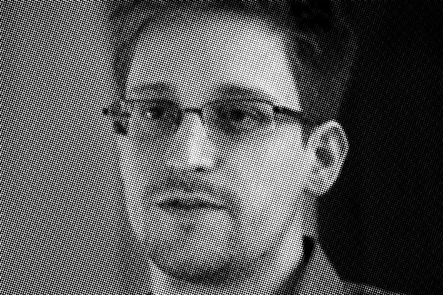

Edward Joseph Snowden (Living Like a Ghost by Abandoning the Empire)

Edward Joseph Snowden (Living Like a Ghost by Abandoning the Empire)

Introduction

Born in 1983 in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, Edward Joseph Snowden worked for the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency and as contractor for the National Security Agency. The U.S. Department of Justice charged him with espionage after he leaked classified documents about the electronic surveillance data mining program PRISM, which he obtained while working for the NSA, to journalists of The Washington Post and The Guardian in June 2013 while in Hong Kong. On June 23, 2013, Snowden left Hong Kong for Moscow, and Russian authorities granted him a three-year residency permit on August 7, 2014.[1]

[1] Edward Snowden is globally recognized and has been discussed and reported on extensively. For this reason, this simple introduction is based on extracts from Wikipedia.

Premise

Edward Joseph Snowden and his leak of classified NSA documents are well known around the world. The long term U.S. monitoring and manipulation of Taiwan, and Taiwan’s subordination to the U.S. in establishing surveillance systems is significant in light of Snowden’s activities. Snowden did not just expose the way the U.S. monitors and manipulates the imagination of global citizens, but also how quick many so-called free and democratic countries are willing to abandon their declarations of universal human rights when faced with the imperialist will of the United States, and therefore denied Snowden asylum. Wanted by the entire global empire, Snowden has not become powerless and vulnerable, but dares to go against the imperialism of his own country and bear the name “traitor” for the rest of his life. This makes him a true dissident, who lives like a ghost and is an inspiration to those who genuinely yearn for freedom and liberty for all.

Snowden holds up a mirror to the collective spiritual chaos of the Taiwanese people who have been accustomed to living in a subordinate position for so long. Leaders of the people who resist regional free trade absurdly appeal to imperialists who advocate neoliberalism and expect its pervasive global authority to even more thoroughly discipline and govern Asia. Do we, like Snowden, dare oppose the logic of consensus that lies between democratic leadership and imperialists? Do we dare reject the democratic leadership, who forces us to remain subordinate to imperialists, in the name of freedom and democracy? Do we dare reject the democratic leadership holding us against our will in the name of patriotism? Before we make art in the name of dissent, should we not first let the spirit of dissent, which is equality, become our real life practice?

There is always more light with a different meaning beyond the spectrum of visible light created by a prism.

Shuiwei (A Place Where Different Time, Space and People with Different Histories Meet)

Shuiwei (A Place Where Different Time, Space and People with Different Histories Meet)

Historical Background

Shuiwei is a shoal formed by the Jinmei and Xindian Rivers and the location of the Lin family residence in the Xindian District. The Kuomintang government built three military dependents’ villages on the site in 1962 to house the many soldiers that retreated from mainland China after the Chinese Civil War, thus making this partially closed off shoal a multicultural site. This narrow slip of land was also the site of a military court and prison which tried and housed political prisoners during Taiwan’s martial law, anti-communist, cold war period, as well as the site of a sanatorium for captured volunteer soldiers from China during the Korean War era. During the Vietnam War, it served as the site of an American logistical munitions factory that manufactured light artillery and bullets. Later, when Taiwan became a world manufacturing center, it was processing area and place where illegal housing was constructed by low wage laborers.

In this tiny place which can be covered on foot in less than ten minutes, one can see traces of the Chinese Civil War, Korean War, Vietnam War, and the period when Taiwan became a global export processing zone under capitalism’s international division of labor. It was also the site of discipline and governance in forms including a prison, barracks, factory, sanatorium and illegal housing. In the late 1990s, Shuiwei was transformed from partially closed off to an area fragmented by the construction of highways.

Contemporary Interpretation

In 1962, when I was just 2 years old, I moved to Zhongxiao New Village located in Shuiwei with my mother and siblings. I moved away from Shuiwei at the age of 22 after finishing my military service and only returned for holiday visits. Shuiwei was once a place I wanted to escape.

One day when I was 36, I realized that Shuiwei was the source of all my confusion and also a place where I could find answers. Perhaps because I had tried to forget this place for more than a decade, when I re-examined memories, people, events, sounds, smells and atmospheres of the different eras in my hometown, and slowly pieced them together in my mind with the scene before my eyes, it was then that I realized this place was the source of my perceptions. I also found a new starting point for my artwork, which was conducting a personal dialog with people and their visible or invisible realities. Also, every person, place and event has a complex connection to other people, places and events. I didn’t really understand this simple principle until I had enough life experience.

There is no place that is an absolute margin. Anyplace that actively produces meaning is both local and international, and a center beyond existing power mechanisms.

Hesheng (Heterogeneous Assembly and a Multiple-Dialectical Movement)

Hesheng (Heterogeneous Assembly and a Multiple-Dialectical Movement)

Historical Background

The term hesheng (合生) was first used in the Tang Dynasty (618—907) probably to describe a performance form mixing opera, storytelling, chanting and dancing, but scholars have been unable to determine which performance formats the term has described throughout its evolution. For this reason, hesheng is a term with vague meaning.

Contemporary Interpretation

If we put aside historical textual research and just look at the surface meaning of the two Chinese characters in this impossible to define term, we see that they suggest “coming together” and “continual happening.” If we imagine a little further and place hesheng in our contemporary context of biopolitical neoliberalism, then it could be an ideology of multiple dialectics and heterogeneous assembly. This is similar to Laozi’s (604—531 BC) concept of one, which is not the same one as we see in mathematics, but rather means the sustained production of multiple dialectics from the one moment a dialectic starts. A simplified and commonly understood notion of dialectic can perhaps definitively be the meaning to which hesheng refers regardless of its performance format. The term hesheng still has the power to inspire. It is a word difficult to define and continually produces new dialectics; it serves as both a method and aim.