Military Court and Prison

2007—2008

35mm transferred to DVD.color.sound.62’ 48”.single-channel video + documentation

Artwork Context and Introduction

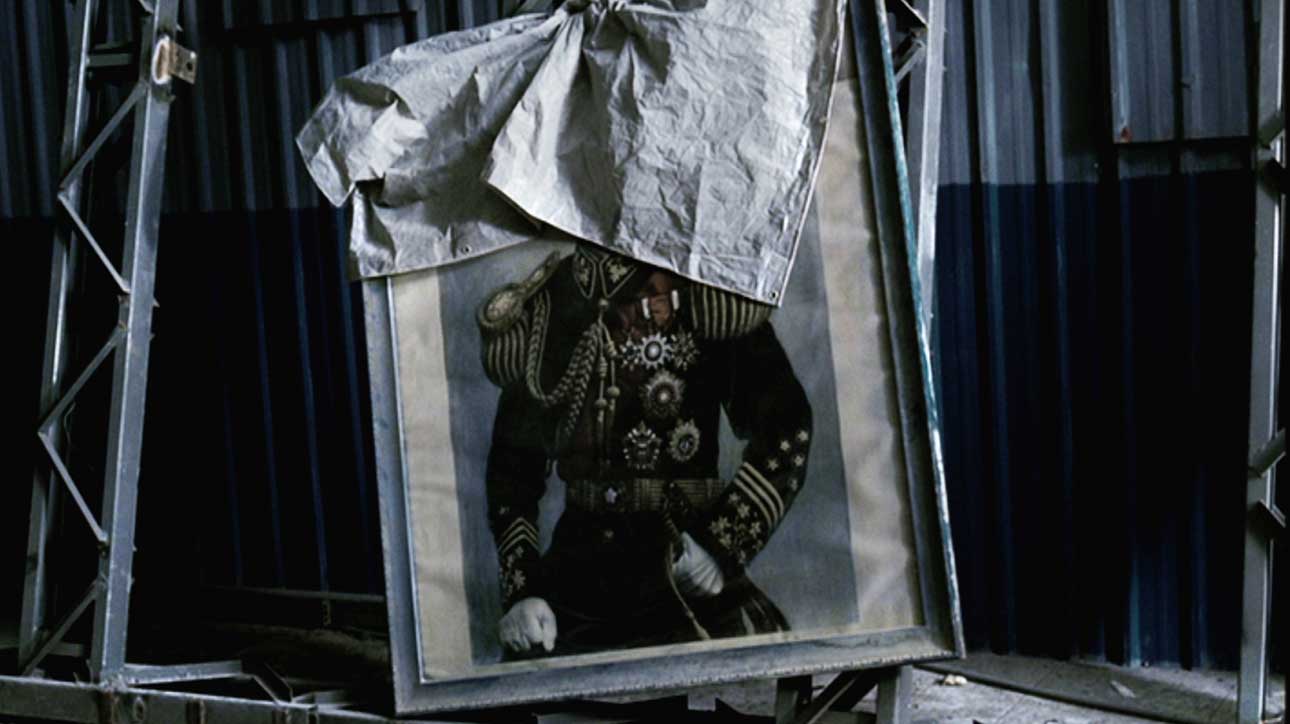

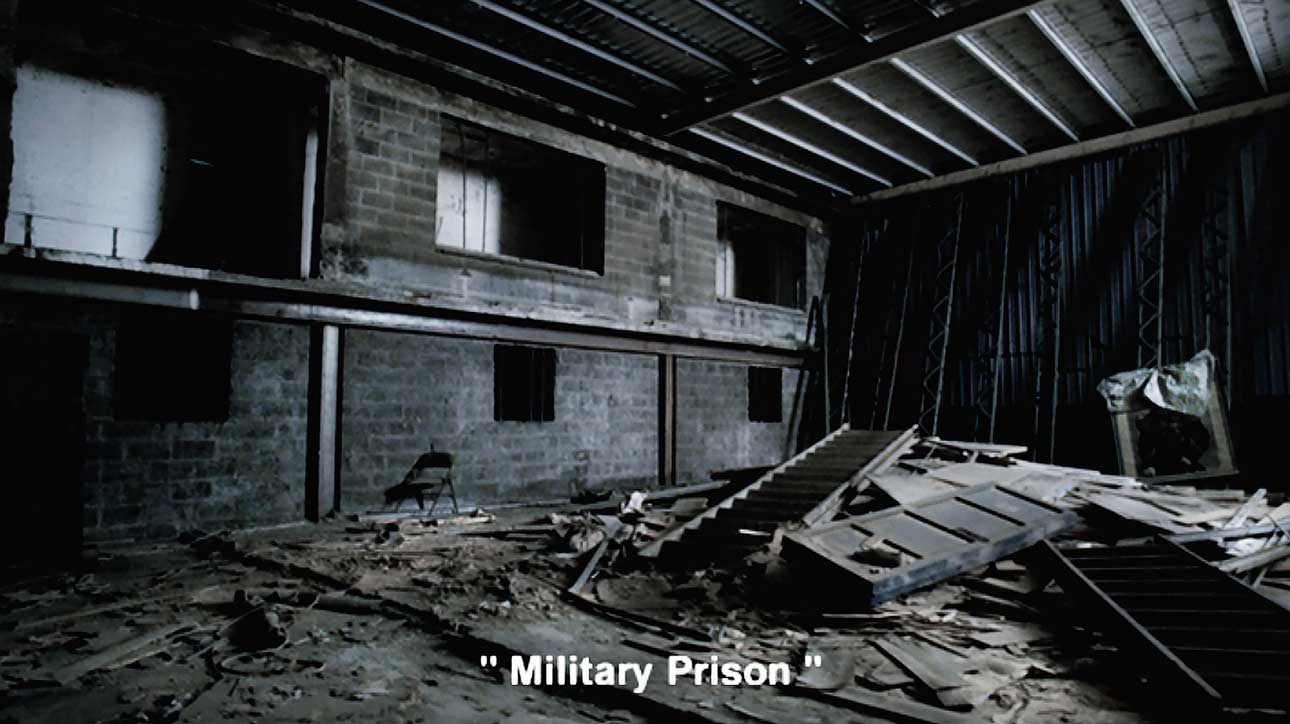

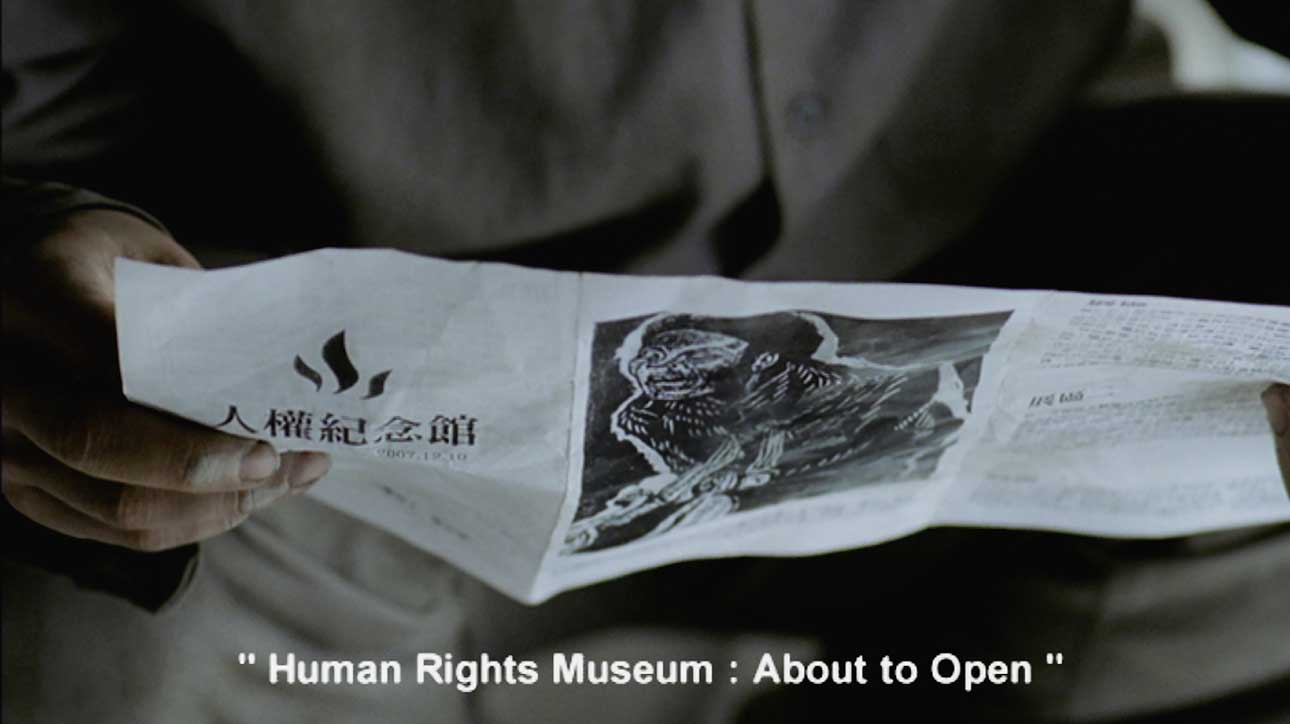

The setting for Chen Chieh-jen’s film Military Court and Prison is the moment when a military court and prison located across from his childhood home was converted to a human rights memorial.(1) During Taiwan’s martial law period (1949—1987), the Kuomintang used the facility to sentence and incarcerate political dissidents, and thus carry out national violence. After 1987, the structure was no longer used to house prisoners, and in 2002 was registered as a historic site by the then ruling Democratic Progressive Party. On December 10, 2007, the building and its grounds officially opened as the Jing-Mei Human Rights Memorial and Cultural Park.(2)

Despite the establishment of the memorial, essential files related to white terror are missing and have most likely been destroyed or locked deep within the offices of the National Archives Administration. Neither the Kuomintang nor DPP has publicly and transparently sorted out the history of white terror in Taiwan, which has resulted in endless controversy regarding transitional justice and human rights since the opening of the memorial.(3)

In the name of transitional justice, Chen believes the government should not only make all files related to white terror public, but also reconsider national mechanisms of discipline and governance deployed throughout its history. With its cold war, anti-communist, and martial law mechanisms, the Kuomintang brutally oppressed and meted out long prison terms to political dissidents, and surgically excised the thinking ability of other citizens. These acts all but obliterated the possibility of dialog between citizens and dissidents, the ability of citizens to imagine alternative value systems, and dynamism in society. The government also deployed capitalist development and new governance technologies to render citizens as conspirators in promoting its ideological objectives, as docile low-wage laborers, consumers pursuing consumerist desire, defenders of post-martial law neoliberalism, and as promoters of Taiwan’s consciousness of domestication.

With his film and from the perspective of contemporary Taiwanese society, Chen raises dialectical questions about this site of past national violence, and current, officially sanctioned historical consensus: Do national mechanisms perpetuate a prison without walls? Does the neoliberalism promoted by government and capital still surgically excise the thinking ability of Taiwan’s citizens?

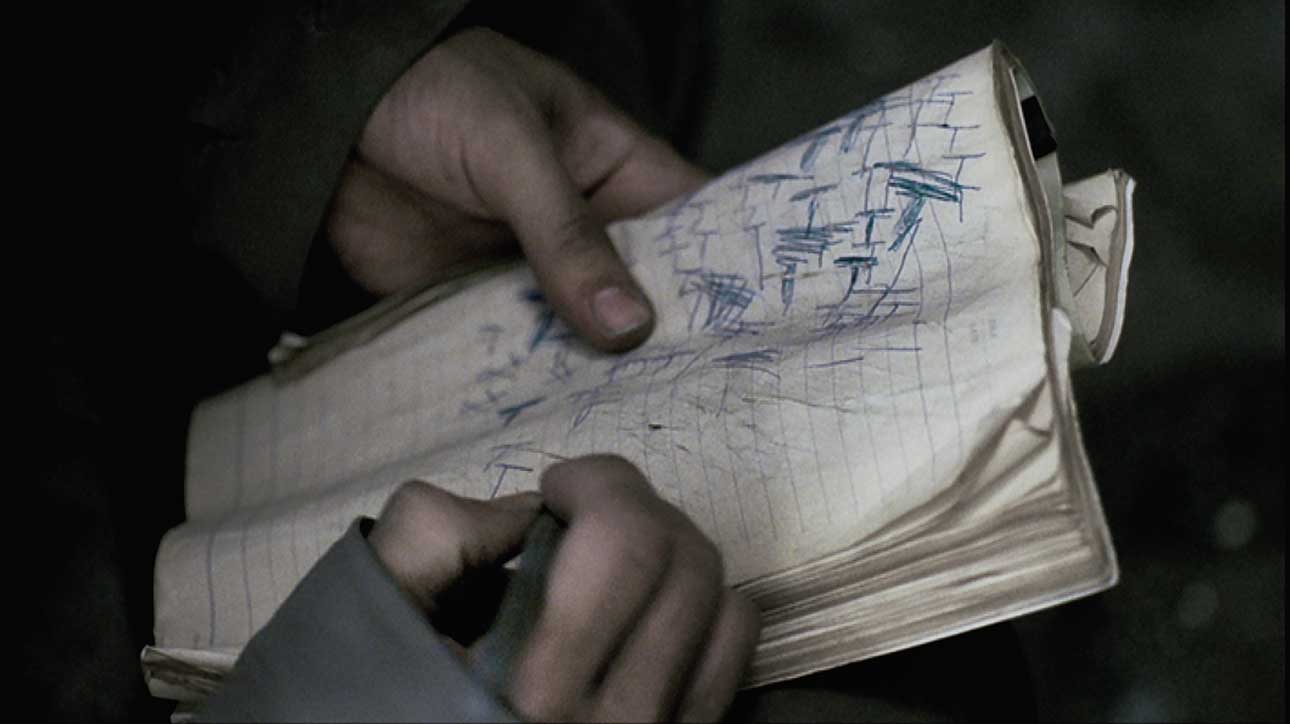

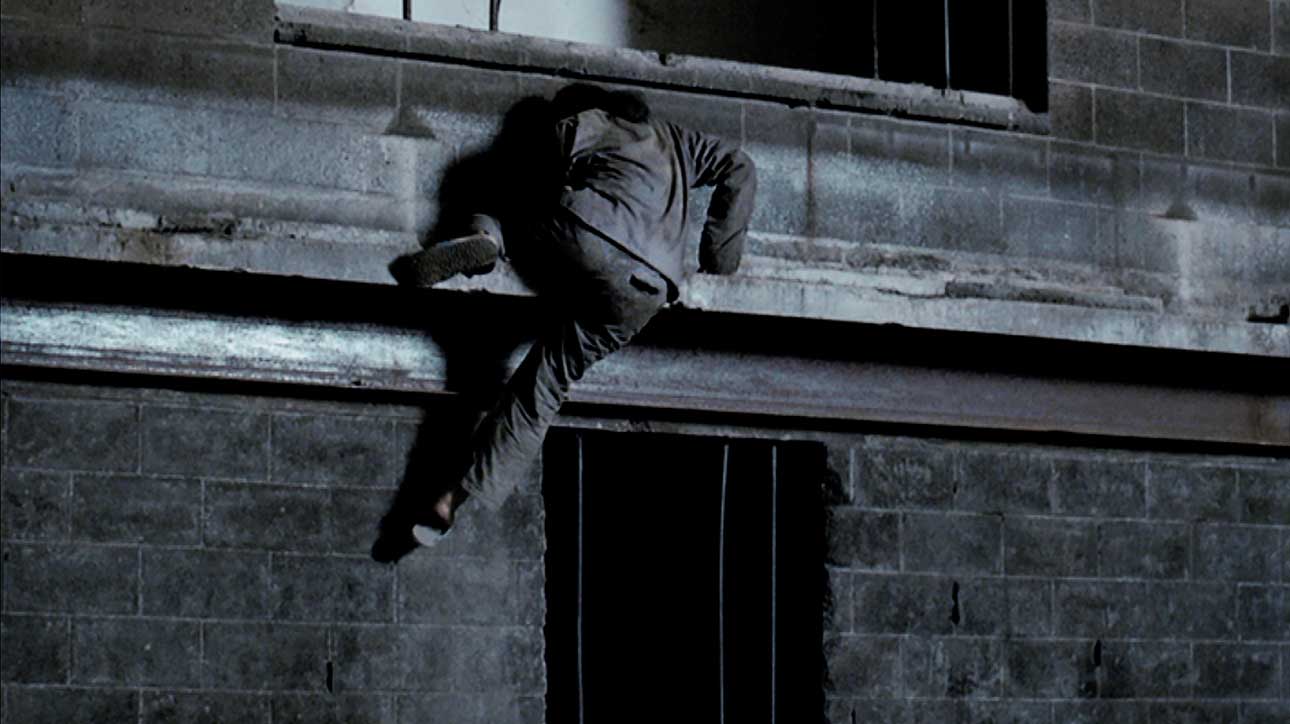

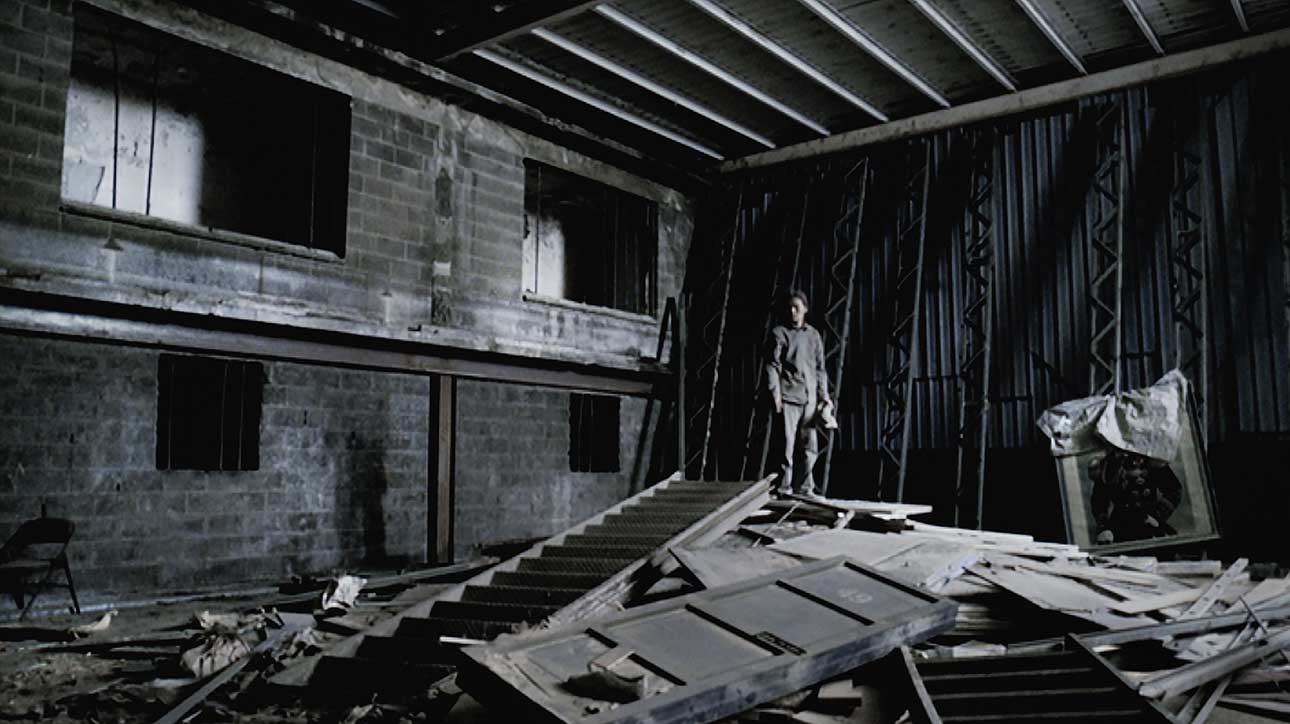

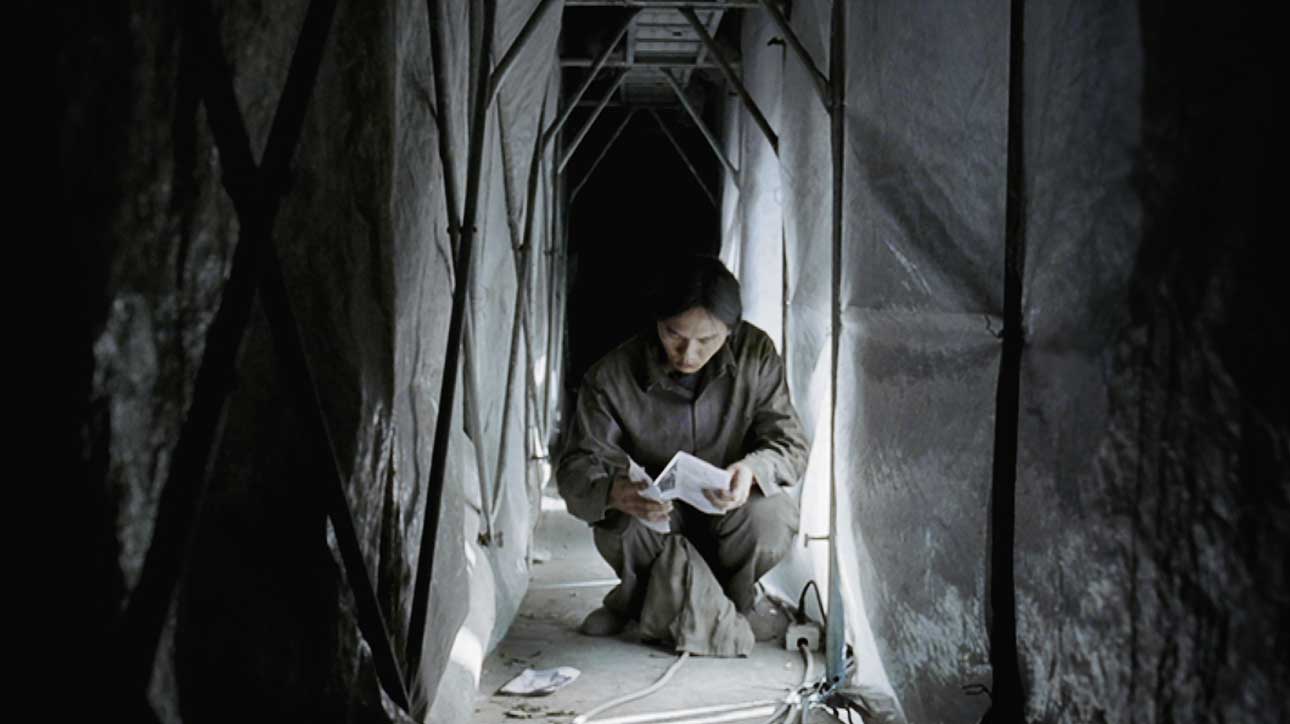

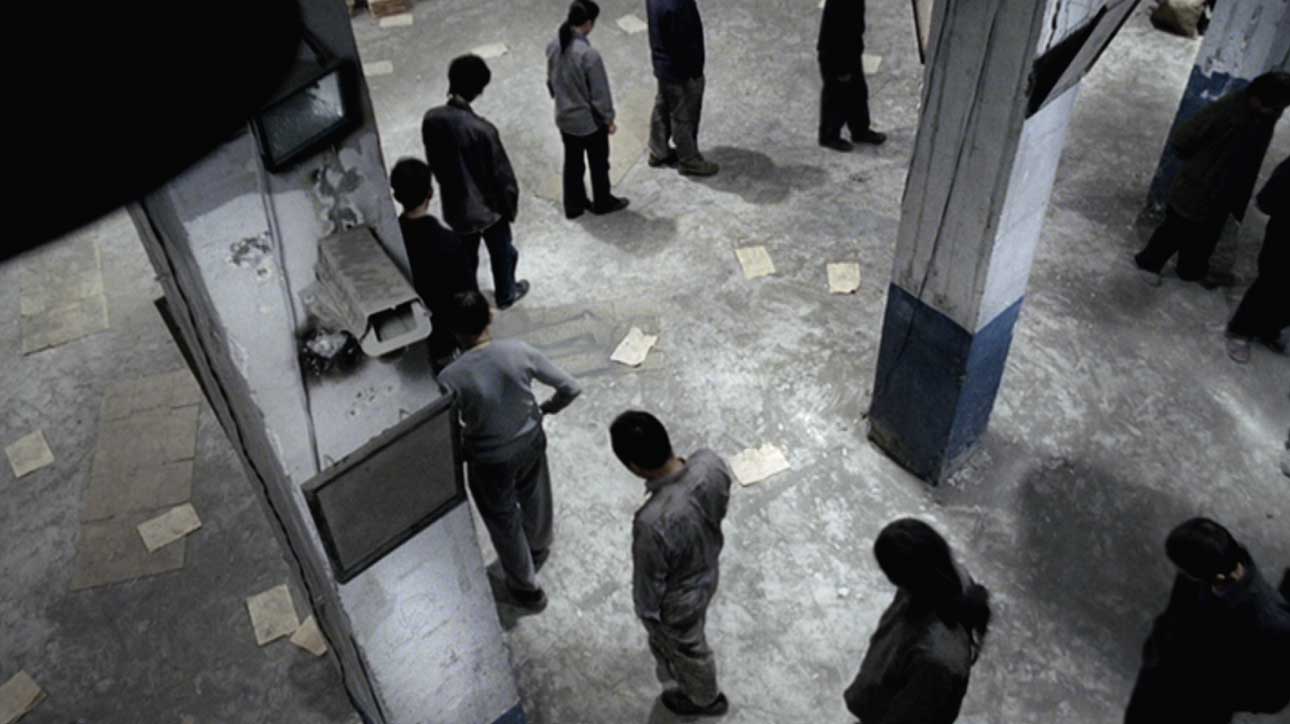

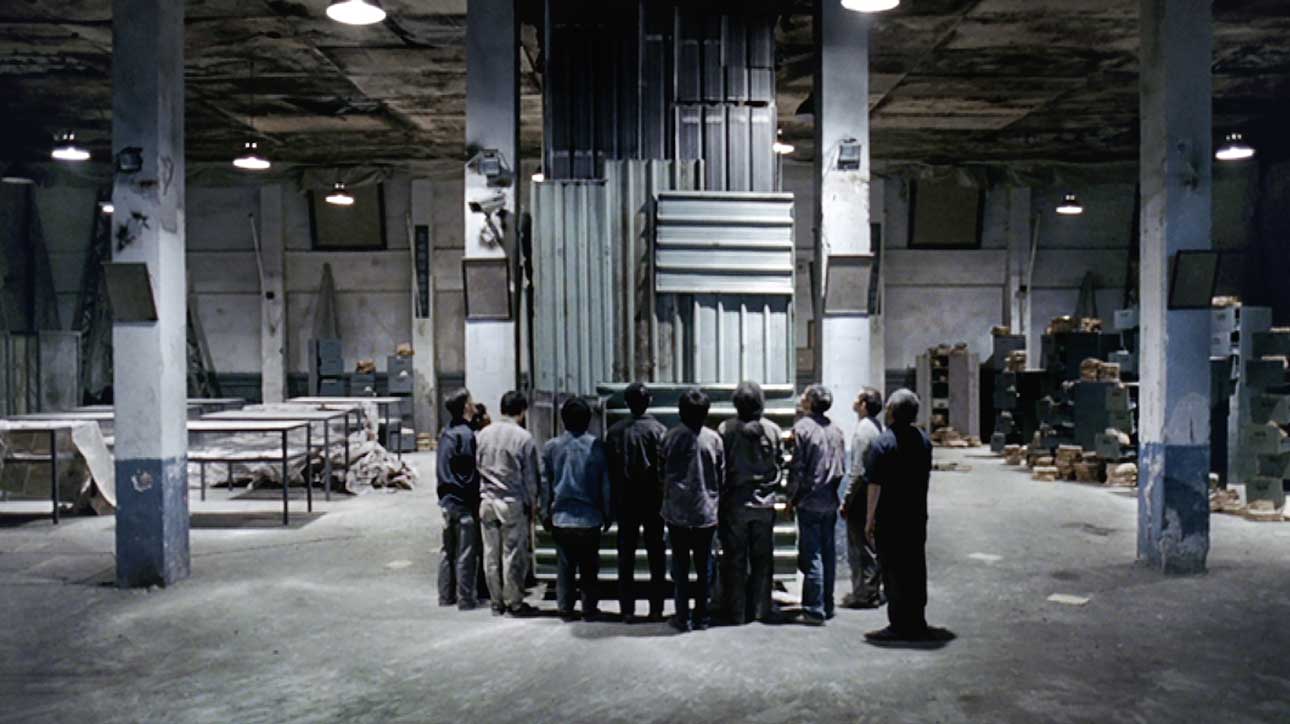

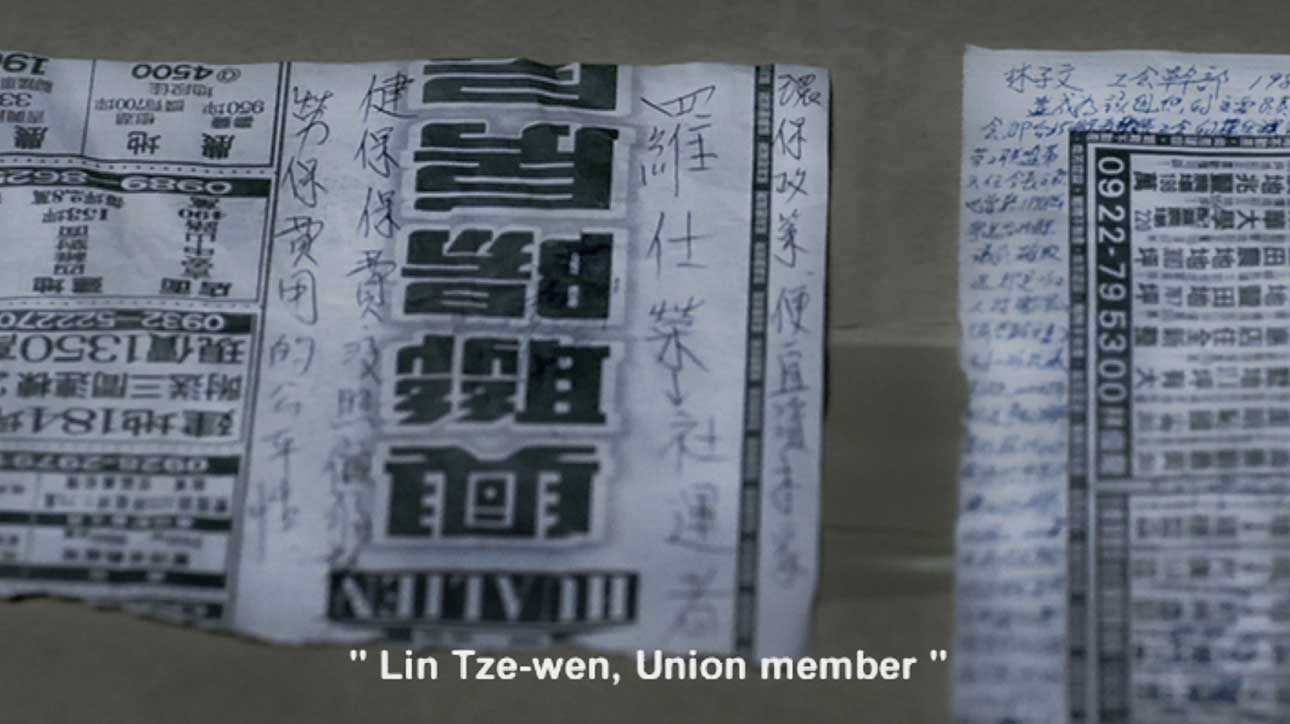

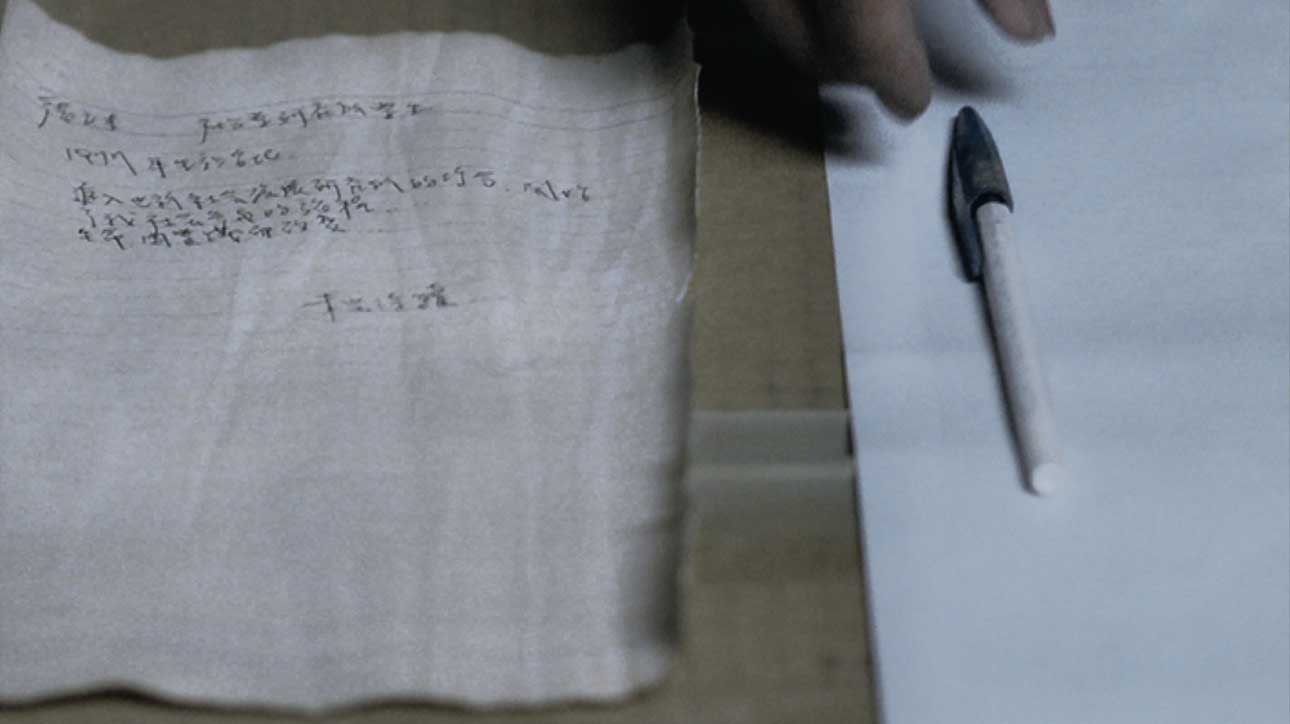

Chen created a fictional narrative and used performance formats from film, theater, and performance art for his Military Court and Prison. The story follows a political prisoner who has been left behind after the prison closes and sees unemployed laborers, migrant workers, foreign spouses and homeless people locked inside the same building. Still enclosed within this space that has been a court, prison and memorial, they all struggle to push a sheet metal structure that appears to be a surveillance tower or temporary worker housing.(4) Loud scraping sounds are emitted as people and metal collide, and then the action abruptly comes to a halt. After this evocative ending, the performers revert to their true identities of unemployed laborers, migrant workers, foreign spouses, homeless people and a social activist, and write their names and plights of being marginalized on the business pages of a newspaper. At the end of the film, the activist who portrayed the anonymous political prisoner leaves pens for the others to continue writing on the blank sides of government forms. Through this final image of unfinished and yet to continue writing, Chen suggests that the dissent of individuals living in contemporary society’s prison without walls under national and capitalist domination can create gaps through linguistic and nonlinguistic means.

Notes

- Military Court and Prison was commissioned by Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofía in 2007. In the same year, Spain’s legislature passed The Historical Memory Law to re-examine the Franco dictatorship (1936—1975) and establish a provision of aid to the victims of white terror under the Francoist regime. Similar to situations in Taiwan, this transitional justice legislation resulted in conservative political backlash.

- From 1957 to 1967, the facility was used for the military law school. In 1968, the Taiwan Garrison Command transformed it into a military court and prison for the processing of political prisoners and military personnel. Most prisoners referred to the facility as either the Jingmei or Xindian detention center, while residents of the area called it the military court and prison. For further details regarding the history of the facility, see (Chinese) http://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/景美人權文化園區, or (English) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jing-Mei_Human_Rights_Memorial_and_Cultural_Park [Accessed May 10, 2024]

- At the official opening of the Taiwan Human Rights Memorial, members of Losheng Self-Help Organization and others protested the government’s demolition of the Losheng Sanatorium (a residence for sufferers of Hansen’s disease). In 2009, the ruling Kuomintang government renamed the facility as the Jing-Mei Cultural Park, a move which incited immediate, violent protest by victims of martial-law period white terror. Ultimately, the facility was renamed as the Jing-Mei Human Rights Memorial and Cultural Park.

- The video was not shot in the actual military court and prison, but on a set built in an abandoned factory which was about to be demolished. Operating in a society where discipline and governance are increasing hidden, Chen felt that he could only fulfill his mission of re-realizing connections among a site of national violence, a human rights memorial and a contemporary prison without walls by designing scenery rather than filming on location. He also felt this was a way of objecting to the current governance model in Taiwan. This was the first time he used a set to shoot one of his films.