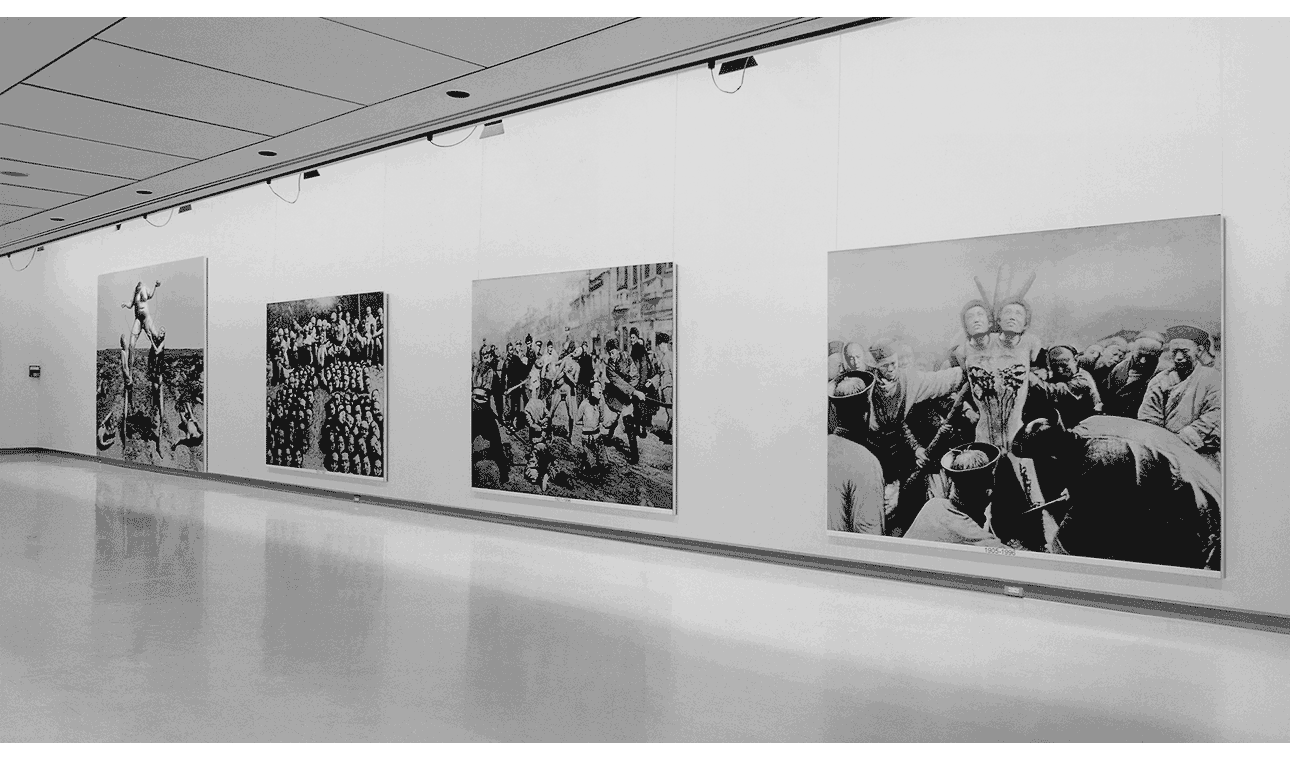

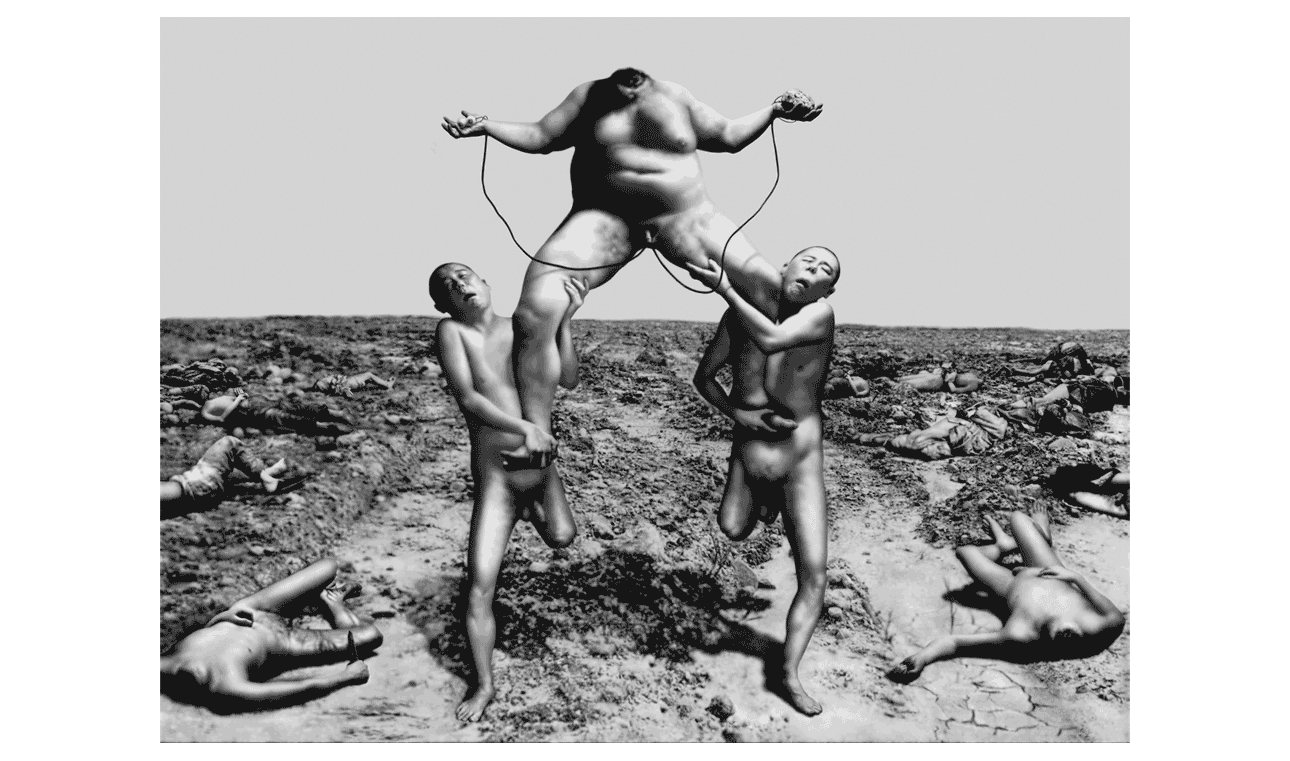

Revolt in the Soul and Body 1900—1999

1996—1999

black & white digital imagery

Chen Chieh-jen created his digital image series Revolt in the Soul and Body, 1990—1999 by adapting (redrawing/rewriting) photographs of public torture and mass killings taken in mainland China and Taiwan between 1900 and 1949 by imperial forces, western anthropologists, reporters, and Kuomintang photographers. Chen utilized blurry, poor quality photographs, which were pirated by publishers during Taiwan’s martial law period (1949—1987), first enlarging the Ben-Day dot pattern of these printed images, and then subjectively redrawing/rewriting them with a digital pen and computer graphics software. In this work, Chen discusses the hidden history of the photographed, which is difficult to discuss since there is no empirical evidence.

Interview Excerpts(1)

After a long break, I start making art again in 1996. I was thinking back to the first time I had seen painting, film, television, and Taiwanese open-air theater. I thought about the meaning of these works, and about the social conditions I was living under when I had seen them. Consequently, some long neglected memories started drifting through my mind. Although human memory is fluid, always having its additions and deletions, mistakes, gaps, imaginative characteristics, and instabilities, it still is one aspect of how we exist at any given moment.

Mirror of Evil Deeds

I remember the first time I saw a painting that made a profound impression on me. Before starting elementary school, I attended my grandmother’s funeral(2) and saw traditional religious paintings of The Ten Courts of Hell.(3) Especially stirring was the center of the first painting, where the dead are kneeling and facing the same direction as if they are watching a film but are actually staring into a mirror of evil deeds, which is replaying in detail all of their transgressions in life. The mirror has the power to make apparent all the deviant thoughts and desires that drifted through the minds of these spirits when they were still living, and in the painting, Yama (king of the Ten Courts of Hell) is using this evidence to decide the fate of these spirits. The painting made me think of how the feudal ruling and religious classes had known about the use of images for discipline and administration before photography was invented. But I was even more curious about the dead who are being brought to trial, specifically how they might be dealing with the question of how Yama is sentencing them based on those seemingly deviant thoughts and desires projected by the mirror. In other words, the same image can produce completely different perceptions and points of view based on the viewer’s position, values and experiences. Therefore, to me, the mirror was destined to suggest paradoxical meanings.

Of course there was no empirical evidence for these imaginings, but to people like me, who grew up in the cold war, anticommunist, martial law period, the complexity generated by the image of the mirror of evil deeds could never just stop at mere spectacle—it was foreboding. It seemed to be saying people are under long-term surveillance and control. This is especially the case under our current era of technocapitalism, where a variety of surveillance and control systems are everywhere. Today, the mirror of evil deeds seems increasingly real.

Medicine Means Poison

Tools are like the mirror of evil deeds; they are complex and paradoxical, and inherently constructive and destructive. Their benefits are extolled when they are invented, but always possess a negative side beyond what is claimed. The invention of the image-making devices has been the same. While cameras can record and capture reality, fix time, preserve memories, and can render individual consciousness, imagination, and perceptions as visible images, they can also be used by the ruling classes as tools of discipline and administration against society and individuals. Taking this a step further, cameras can also be used to produce evidence of manipulation of the social imagination and individual desires by the ruling classes. And differentiating the use of negative film from digital photography, we find each has its unique features. The exposure and then developing of film in a darkroom is much more transparent than the digital process. But using film also places limitations on image editing, and therefore also limits the possibility of altering or reinterpreting the point of view of the photographer, which is a possibility that might otherwise be advantageous to those who are photographed, disciplined, or administered by the use of image-making devices. The lack of transparency in the digital photography process makes the images it produces susceptible to limitless revision or intervention. In other words, altering the film used in the transparent photography process is difficult, and therefore its images are mostly frozen and unchangeable. But since its invention, the not so transparent process of digital photography has rendered the image easily changeable.

But my concerns are with those who cannot have photography equipment. How can they confront and transform the way the ruling class uses images to discipline and administer them? Furthermore, is there a way to allow different points of view to develop or to facilitate confrontation and unfolding multiple dialectics? If so, can this be accomplished by using the constructive/destructive paradox of image creation equipment? Or can we keep splitting this paradox to achieve these confrontations and produce these dialectics?

Empty Form, The History of the Photographed

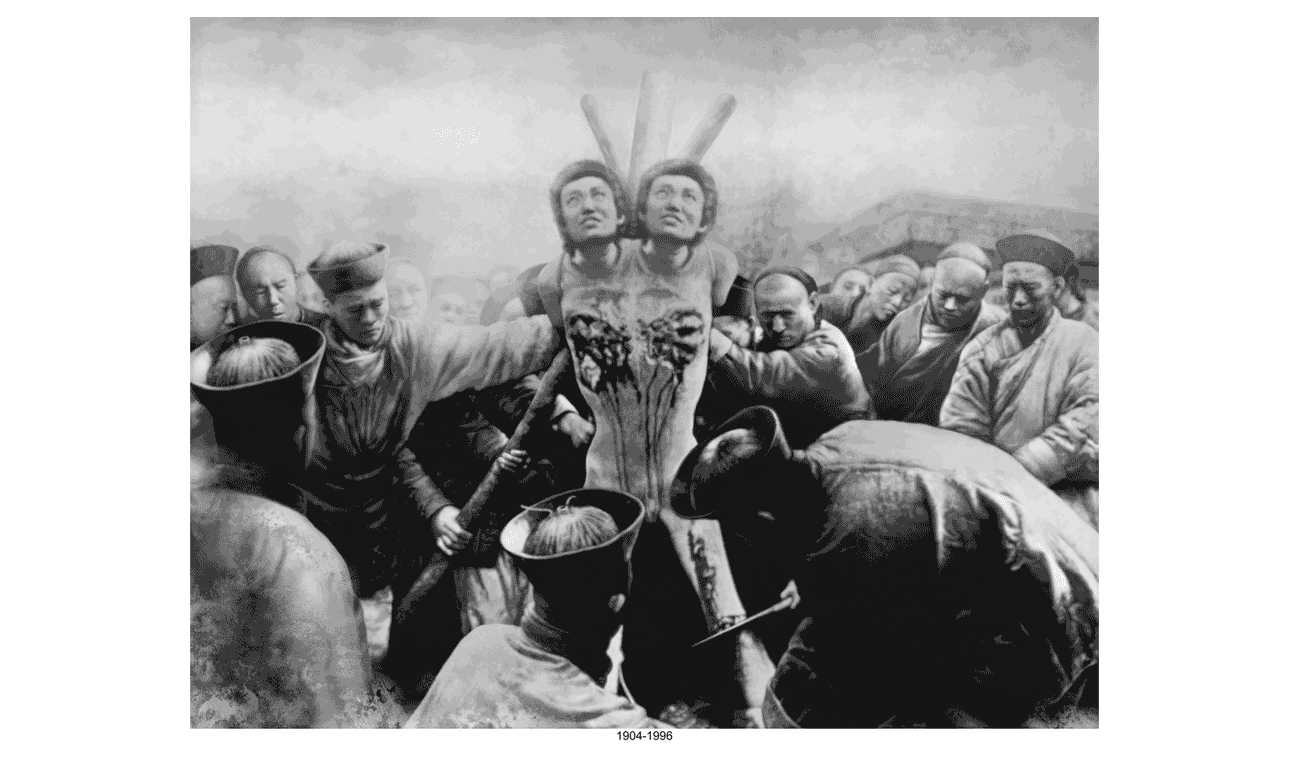

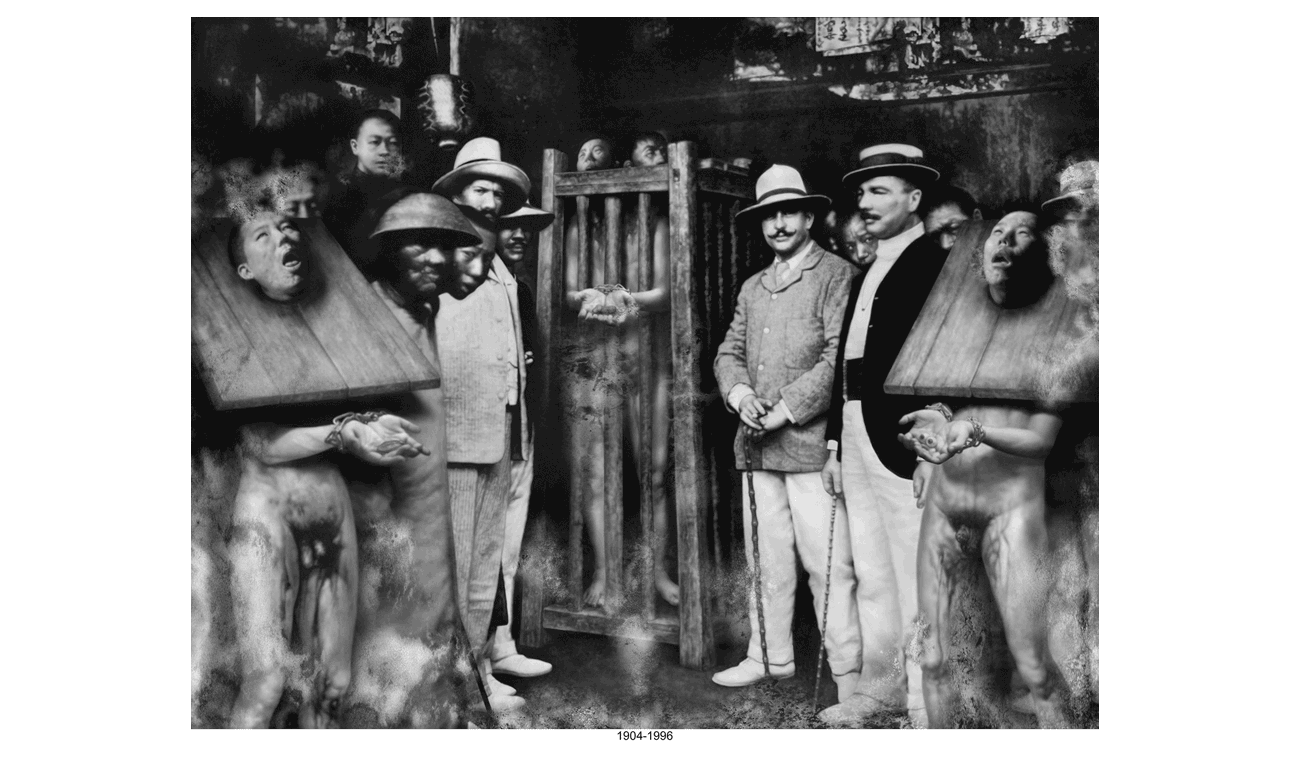

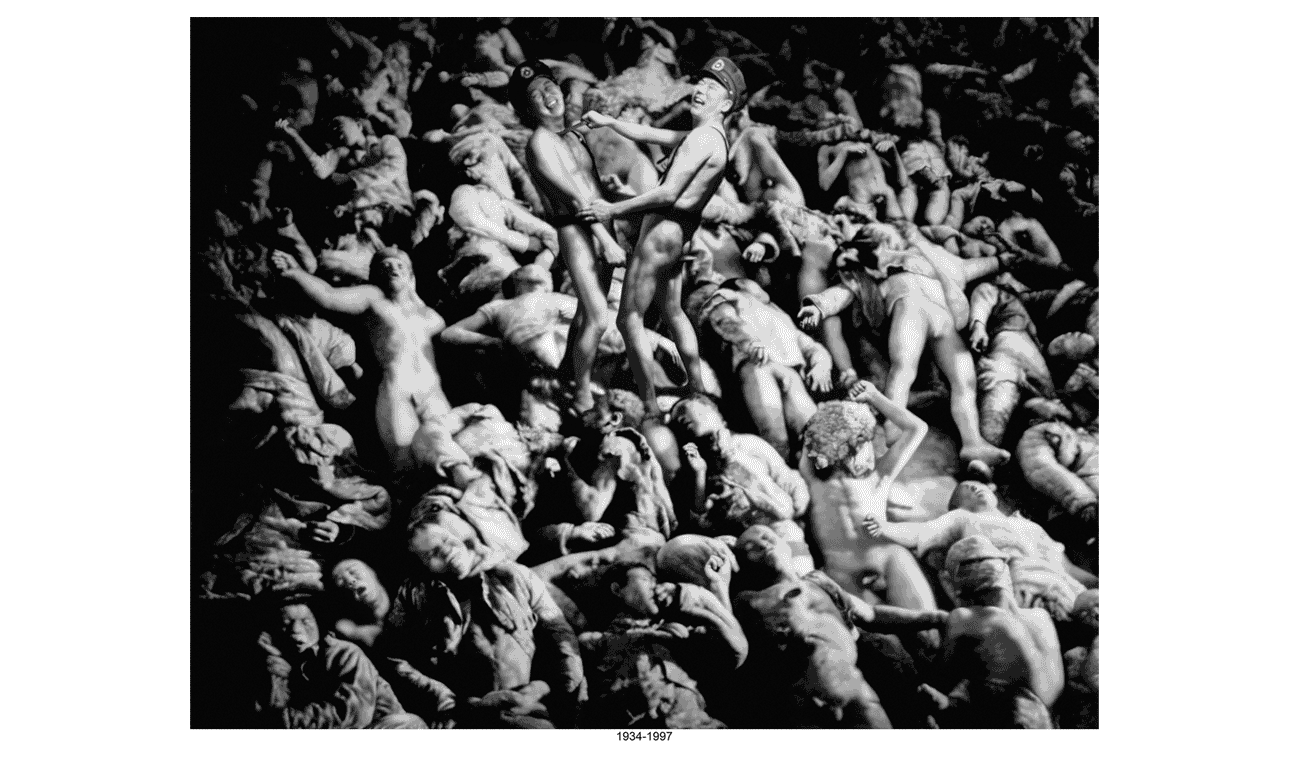

Why, after making art again in 1996, did I choose to use a computer to re-depict or rewrite pictures of torture and massacre as my starting point? I made this decision after running into a friend on the street whom I had not seen in many years.(4) Starting in around 1988, I became increasingly confused about how art production contexts and methods might be developed in non-western regions, and then gradually stopped making art and quit my job. In the eight years of unemployment that followed, I sold off my photography equipment and materials. I was nearly destitute when that friend I ran into generously offered to let me use his 486 computer and teach me (for free) the basics of how to operate it and use drawing software. Afterwards, I used my questions about the accepted history of photography as a starting point for new work. Simply put, as someone living in a non-western region, my uncertainty centered on the time when photography equipment was carried around the world by colonialism. People living in non-western regions at that time were entering the early history of photography as the photographed, and history ignored their responses to this new technology and the possibility that they had influence over the content of an image. Furthermore, since images of torture are the most extreme and complex representatives among those of the photographed, I started to think about using computer graphics to discuss the history of the photographed in the history of photography, and to redraw or rewrite complex images of torture as images that could initiate a continually expanding, multi-dialectical movement.

Those early photographs of torture were all taken by western imperialistic military forces, western anthropologists, or western reporters, and for a long time, were interpreted through a lens of western centrism. They served as “legitimate” evidence of savagery, cruelty, and primitivity in non-western regions, which were therefore in need of western enlightenment. Later, as anti-colonial movements unfolded, discussion of these pictures was put aside under the prevailing view that they were just sought out as novelties in an atmosphere of orientalism and western ethnocentrism.(5)

By the 1990s, critiques of hierarchical views of world civilizations were common in academic circles, but for those of us living in non-western regions, the question of whether the complexity of those images of torture could be explained away as “orientalist novelty seeking” still remained. We wondered if we could deepen assessments of neo-colonialism and internal colonialism by revisiting the complexity of those images and critiquing orientalism. Today, we must first excavate and discuss those images now that capitalism has replaced traditional forms of visible torture as a means of administration, and imperceptibly continues to extend its control over our daily lives. In other words, when undertaking an analysis of today’s naturalized and numbing forms of torture, we must first look to torture in its traditional and visible forms, as the continuity and dialectical relationship between the two cannot be ignored.

The complexity of those excavated images demands a reevaluation of the history of photography, starting with its framework composed of the invention of photography, the views of those possessing cameras, and critical interpretations, such that multiple perspectives can be incorporated. It must be remembered that until the 1970s or later, few people in non-western regions owned cameras, which means that for more than 140 years after the invention of photography, the vast majority of those people were relegated to the position of the photographed. I do not wish to oppose the history of photography, or suggest that owners of photography equipment or professional critics belonged to a privileged class, but rather to say that the photographed exist within the history of photography, and that an enormous gap has been left in history by neglecting a discussion of them for so long. A description of the gap is perhaps all that is needed to incorporate heterogeneous perspectives arising from different historical contexts, stages of social development, and life experiences into this history.

Images of Torture and Multiple Identities

I first encountered pictures of torture and massacre when I was in elementary and secondary schools. To prop up their legitimacy, the Nationalist Government (KMT) mandated anti-communist education in elementary and secondary schools, which occasionally took the form of traveling propaganda exhibitions depicting the recent histories of Taiwan and mainland China from a KMT perspective. They always included images of victims killed in war or by public execution from the time of the Opium Wars (1840—1842) to the Cultural Revolution (1966—1976). An image of torture in one of those exhibitions left a deep and unforgettable impression on me. A victim of lingchi torture (a form of execution in which a knife is used to remove portions of the body over time, eventually resulting in death) filling the frame was still alive and had what seemed to be a faint smile on his face. His torturers and others were mostly outside the frame, but that smile entered my mind and has never left. I remember the caption stated that he was a soldier in the anti-Japanese volunteer army and was being tortured by the Japanese military. Regrettably, I do not remember his name and have never seen this picture since. The memory, however, led to my use of an image of lingchi that appears in Georges Bataille’s Les Larmes d’Eros in my digital image series Revolt of the Body and Soul 1900—1999, which was my starting point for redrawing and rewriting images of torture. Later, when I saw photographs from Taiwan’s white terror period, I noticed that many of those communist party members and political dissidents carried calm expressions or were faintly smiling as government photographers captured their last moments of life before being executed. This made me think that this unusual and silent smile has been passed down through generations of unacquainted dissidents for reasons that can never be known.

The basic elements of traditional torture photographs include the victim, observers, the torturer and assistants. Elements not in the image include the photographer and the government official who ordered the execution. In other words, this group representing the politics of death is composed of a law breaker, anonymous observers, executioners necessarily occupying a lower rung in the penal system, an image recorder who has mastered a certain technology, and those who maintain the authority and smooth operation of the administrative regime. This cross section is reminiscent of Michel Foucault’s many enlightening analyses of the evolution of disciplinary techniques in his book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. But being a careful observer of a photograph instead of being present at the execution, I cannot help but wonder what my role might be in this mechanism of authority. Likewise, I wonder what my role might be in today’s naturalized and numbing forms of daily administrative mechanisms. What status has been assigned to me without me knowing?

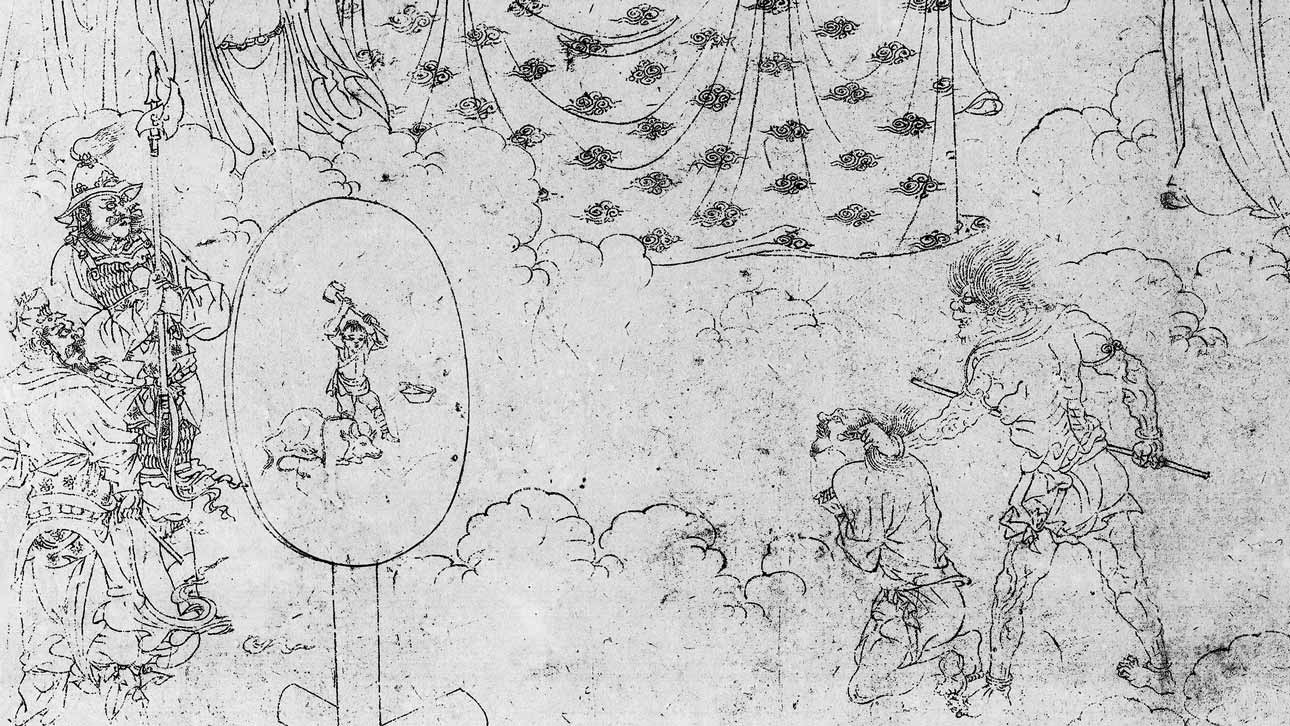

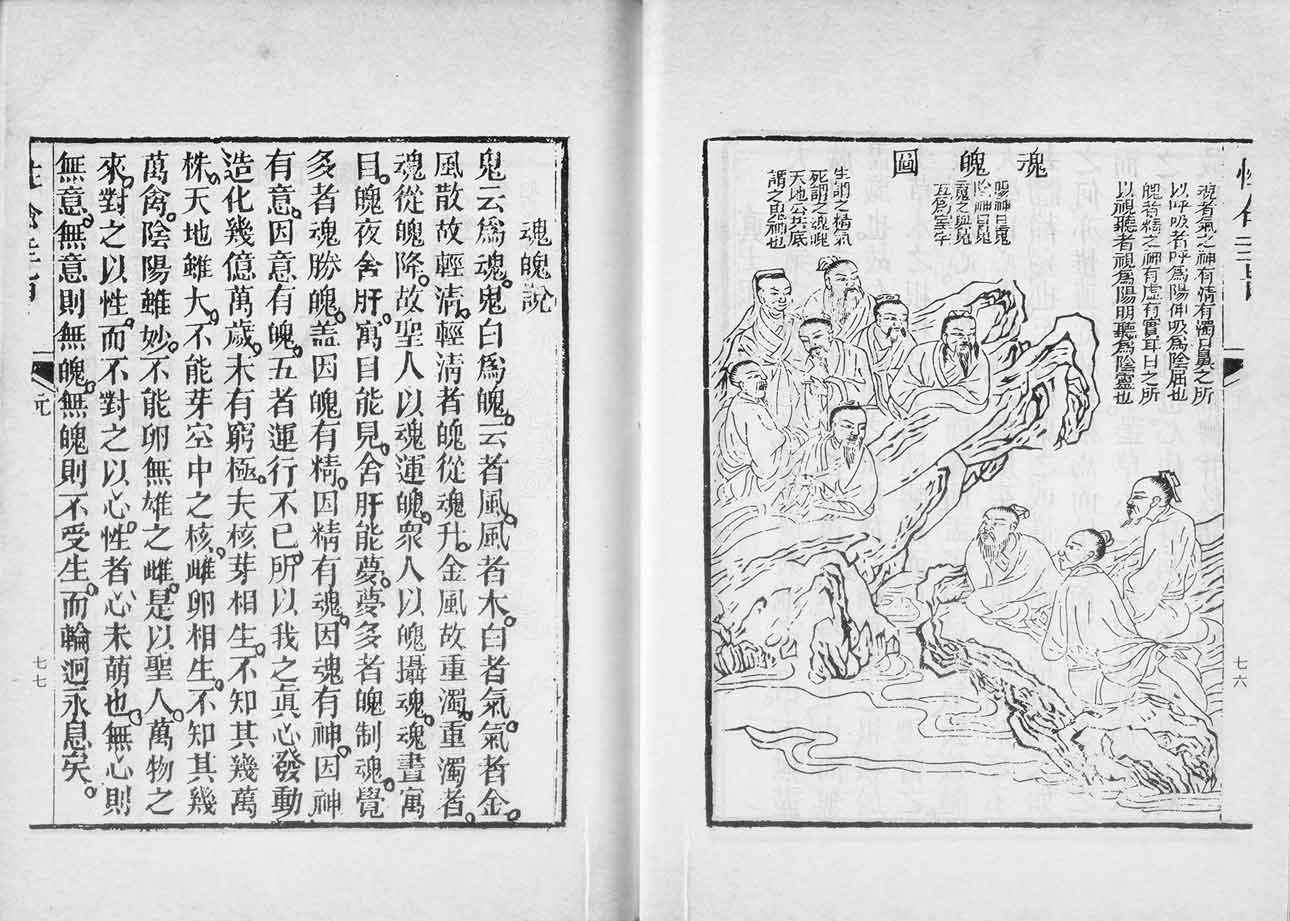

While engaged in this reverie, I was reminded of the significance of the Chinese character “我” (wo). In addition to meaning I, which comprises both an individual’s body and mind, wo also refers to the Taoist and folk beliefs that claim a being is composed of three ethereal souls and seven corporeal souls. These seven corporeal souls, which correspond to happiness, anger, grief, fear, love, disgust, and desire—appear on the Taoist Hun-Po Chart in anthropomorphic form.(6) They are painted as seven figures whose features show no emotion, such that determining which figure represents which mortal form is impossible without consulting the explanations on the chart. However, in my opinion, this probably is unrelated to the painter’s skill at rendering emotions, but rather was done deliberately. For an individual, an emotionless expression is the default, but one of the seven mortal forms may appear in response to some event or the behavior of another person. In other words, an emotional response is the result of some external circumstance, such as another person’s influence, entering the psyche, or wo. Therefore the ancient Hun-Po Chart suggests that multiple others with similar appearances but different personalities exist within each individual. Following the same line of thought, a native language is never truly native because it does not come from a single source, but from the continuous admixture of different languages over the long course of history. In other words, there exist multiple others that are impossible to measure and of unknown provenances within the individual (wo) and also within the language that the individual uses.

The multiple others that exist within us remind me of the Double-Headed Buddha sculpture dating to the 13th—14th centuries.(7) According to my lay understanding of Buddhist doctrine, a two-headed Buddha suggests that the past and future coexist since time passing in the current moment also includes past and future moments. Likewise, we are conduits through which different times continually pass.

Following these thoughts, I realized that within us all exist the victim, bystander, executioner, executioner’s assistant, and persons who pass the sentence and document the execution. This conflicted state exists for subjective or objective reasons and regardless of our awareness. This was the case under traditional mechanisms of authority, and is still the case under the normalized and numbing forms of daily administration we live under today. The implication is that everyone (wo) is not only composed of a single identity, but many conflicting and fluid composite entities. Reinvestigating these forms of torture is a basic and reflexive impulse, and offers up for perusal a detailed picture of the impurities within us.

After Suppression Becomes Invisible

Seeing traditional torture raises our awareness of certain issues that are not limited to the study of history. After it was revealed that American forces carried out torture at the Abu Ghraib prison and the Guantánamo Bay detention camp, it became clear that traditional torture had not disappeared. This challenges our view of torture: Do we continue to see it as something from the past or an exception that might occur in a distant war? Or do contemporary instances of torture prompt us to explore or expose how current mechanisms of authority distract us from the naturalized and numbing forms of administration that have become our daily lives. In her essay titled “Regarding the Torture of Others,” Susan Sontag discusses the second Bush administration’s shameless rhetoric aimed at neutralizing the savage acts carried out at the Abu Ghraib prison. In the same essay, she also claims that the circulation of pictures of this savage behavior was done all in fun, and this “fun” is part of the true nature and heart of America. Sontag obviously believed that stopping images of contemporary torture from continually appearing would be impossible in the digital age.

When Sontag was writing this essay, the Bush administration stated that releasing photographs of torture damages the morale of American forces and therefore refused to make further images or videos public. Four months into his presidency and six years after Sontag died, Barack Obama stopped the release of images depicting American forces raping female prisoners or using clubs and electrical devices to sexually abuse prisoners, saying that they stirred up anti-American sentiment and endangered troops stationed abroad.(8) Less than five months later, on October 9, 2009, Obama won the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Development of Revolt in the Body and Soul 1900—1999

Returning to my reasons for creating Revolt in the Body and Soul 1900—1999, I think most of my motivation came from the various difficulties I had encountered in my life. I had a notion that making art might facilitate my understanding of, or help me find the source of, these difficulties, and I also wondered if they might lead to some kind of problem awareness. For example, whenever I read about the history of photography, I wondered why, in whichever version I was reading, there was no mention of the people being photographed. Had I not grown up next to prison for political prisoners during the cold war, anti-communist, martial law period, not seen that mirror of evil deeds at my grandmother’s funeral, not seen that picture of lingchi torture when I was in elementary school, or not read about the Hun-Po Chart or Double-Headed Buddha, then perhaps I never would have thought about the history of the photographed. I was preoccupied by this question for some time before I was able to figure out how to discuss these difficulties in my artwork in a way that does not rely on empirical evidence.

The making of Revolt in the Body and Soul 1900–1999 involved a lot of handwork. First, I scanned poor-quality, pirated images from books into a computer and enlarged them so that their Ben-Day dot patterns could be seen. I then used my imagination and a digital pen to draw on the patterns. At the time, I thought drawing with a digital pen and tablet felt like painting in empty space, which was an emptiness that prevented me from ever coming in contact with the image on the computer screen. This was especially so because the 486 computer I used was extremely slow. Every time I made only a few strokes with the pen, I would have to wait for the computer to slowly process them, and often only a fraction of the marks were registered by the computer. But while I was waiting, I realized that boredom provided an opportunity for my mind to wander, and later I used my down time to come up with ideas for new artwork.

After drawing on those difficult to decipher remnants of images, I then cut them up and collaged them to make two-headed victims and painted portraits of myself as the victims, onlookers and the executioners. This entire process was similar to recreating the appearance of something upon its ruins, but the significance is what I call “cartography of the psyche.” In other words, it is more like using hand labor to revisit a history that took place before I was born. The process of redrawing and rewriting seems similar to the stone-rubbing process that reveals another layer of a historical image, and while it is carried out in the world of a computer, it is also related to the body.

Following the invention of the camera, many photographers used multiple exposures and montage to create multiple selves in the world of the photograph, or to costume themselves and play a role in an opera or fairy tale. Digital image equipment merely produces these kinds of images more quickly, and drives our desire to possess multiple identities. But more than this, I am interested in how to reveal the perceptions, imagination, and dissent hiding within visible objects, so in 1998, I started to think about how to develop and eventually realize this idea.

By 1998, personal computers had entered a new generation with 32-bit processors. As everyone knows, digital technology continues to develop at an astonishing rate, and in the process, people have been completely dominated by it. In late 1998, I thought that 1999 would be awash in white light due to the abundance of digital operations and information, so I just spent a few seconds creating an image composed of white pixels which I titled 1999, and then decided this series was finished.

But rather than the feeling that I had finished, I felt that confusion and problem consciousness increasingly arose the more I made the work. I am sure that this must have been overflowing from what I had wanted to talk about when I started the project, so I was being driven by confusion to the next project all along. It was not until after finishing Revolt in the Body and Soul 1990—1999 that I thought about shooting video using a self-organized community of participants and freely developing modes of presentation. This is the method I used for my later work Lingchi–Echoes of a Historical Photograph and Factory.

I think the day when my confusion finally ends will never come.

Notes

- These excerpts are from an interview conducted by the Taipei Fine Arts Museum in 2011 for a publication project on Chen Chieh-jen. However, only a part of the original interview plan was completed.

- Chen Chieh-jeh’s mother was given in marriage to a household in Kinmen by her Malaysian family when she was five years old. She saw her mother again for the first time more than thirty years later in Taiwan. Neither Chen Chieh-jen’s mother nor Chen Chieh-jen remembers when she passed away.

- These paintings are based on a mixture of Chinese folk beliefs, and Taoist and Indian Buddhist notions of hell, which later developed into a depiction of the structure of hell used in temple paintings. They are often posted to the left and right in places where traditional Chinese funerals are held. Additional information (Chinese) about the history of these diagrams can be found at: https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-tw/%E5%8D%81%E6%AE%BF%E9%96%BB%E7%BE%85 [Accessed May 10, 2024]

- Chen Chieh-jen had met Liao Neng-bin, the friend who helped me with this, when he was working at a subcontracting company in the animation industry.

- Orientalism, published in 1978 and written by the postcolonial scholar Edward Said, is a seminal work in the field of postcolonial studies. But like all classics, it can be oversimplified or corrupted. For example, following Said, some have noted that discussing unfair treatment in non-western regions from a western perspective is problematic. Unfortunately, this use of Orientalism has also hindered reflection and cultural production in non-western regions.

- The seven corporeal souls were originally given names that are difficult to decipher today. Modern versions of these names were taken from Wikipedia; for further information in Chinese see: https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-tw/%E4%B8%89%E9%AD%82%E4%B8%83%E9%AD%84 [Accessed May 10, 2024]

- There are conflicting accounts of the exact source of the two headed Buddha story. Chen Chieh-jen based his interpretation on books about Buddhism that he had read in spare time, and not by directly interpreting the origin of two headed Buddha statue.

- See “Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse,” in Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abu_Ghraib_torture_and_prisoner_abuse [Accessed May 10, 2024]